-“To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability… All photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” - Susan Sontag

Adán Abraján de la Cruz was 24 years old the rainy night he disappeared on September 2014. A first year student at the Ayotzinapa Teacher’s Rural School in the impoverished Mexican southwestern state of Guerrero, Adan went missing along with 42 other students when the buses they were traveling in were attacked by a drug cartel in Iguala. The sicarios handed them to the local police but not for compassion nor security reasons: The police, working in complicity with city officials, later disappeared Adan and his schoolmates. They are now known as “the Ayotzinapa’s 43.”

I followed the family of Adan Abrajan de la Cruz for 6 months in 2015.He had left behind a wife, two children, two sisters, both his parents and two grandparents. I wanted them to tell their own story, so I started a small multimedia project, using interviews, small video clips and still images, for which I asked for personal photos and footage of their missing ones.

But something moving happened. Adan’s relatives had not recent records of their lives. “I don’t have any, I had it my phone, but I lost it,” I kept hearing, time after time. Or “I replaced it and didn’t save the photos.”

Others had the same answers. So one thing became clear to me: Not only they had been stolen from their future, but a memory of who they were was also doomed to disappear. Apart from a few mugshots and blurry, very low res cell phone images, very few of the family members had pictures of their disappeared loved ones. It was shocking: they had no recent pictures because they did not need to keep them. Why? Nobody was going to take their husbands, sons, brothers or fathers away.

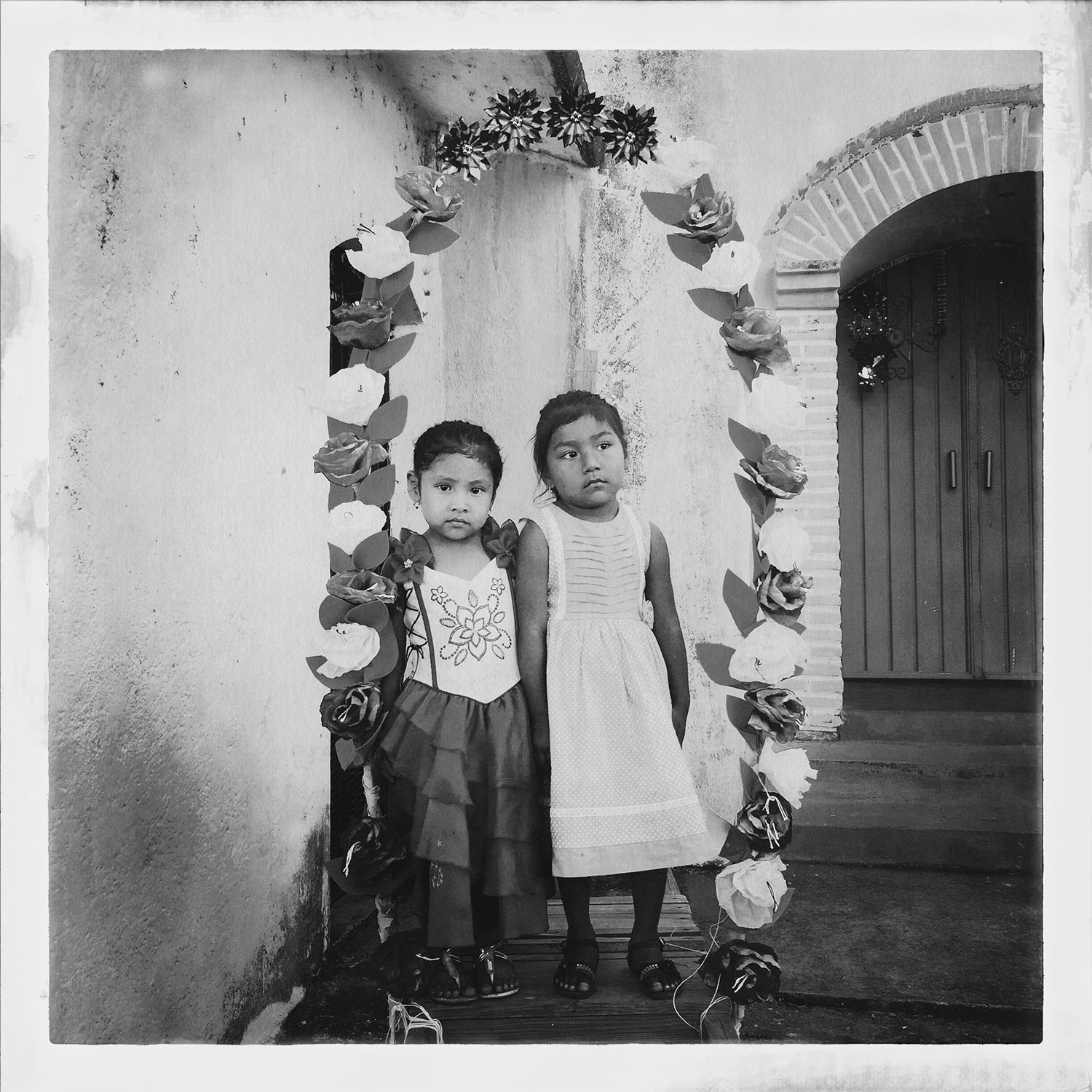

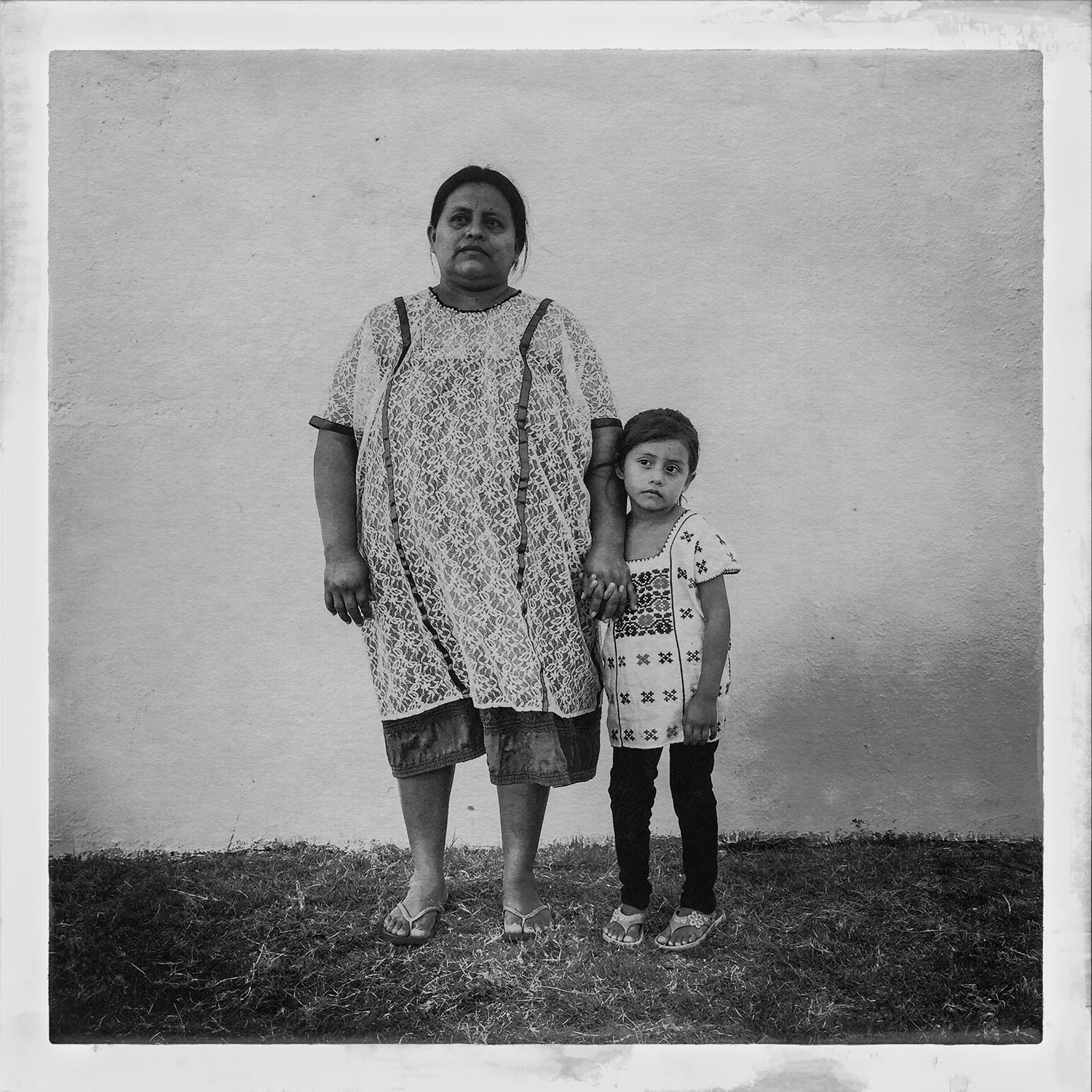

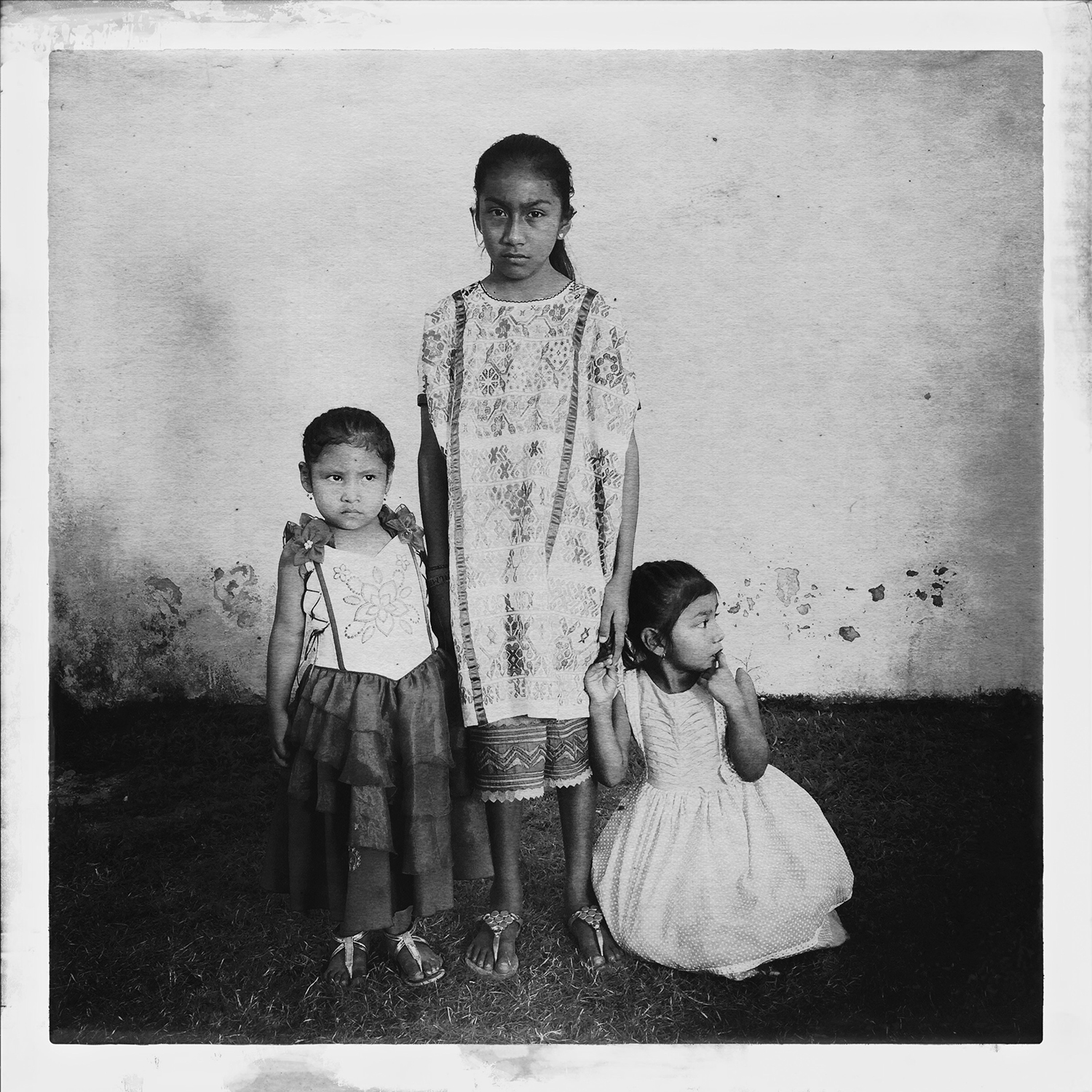

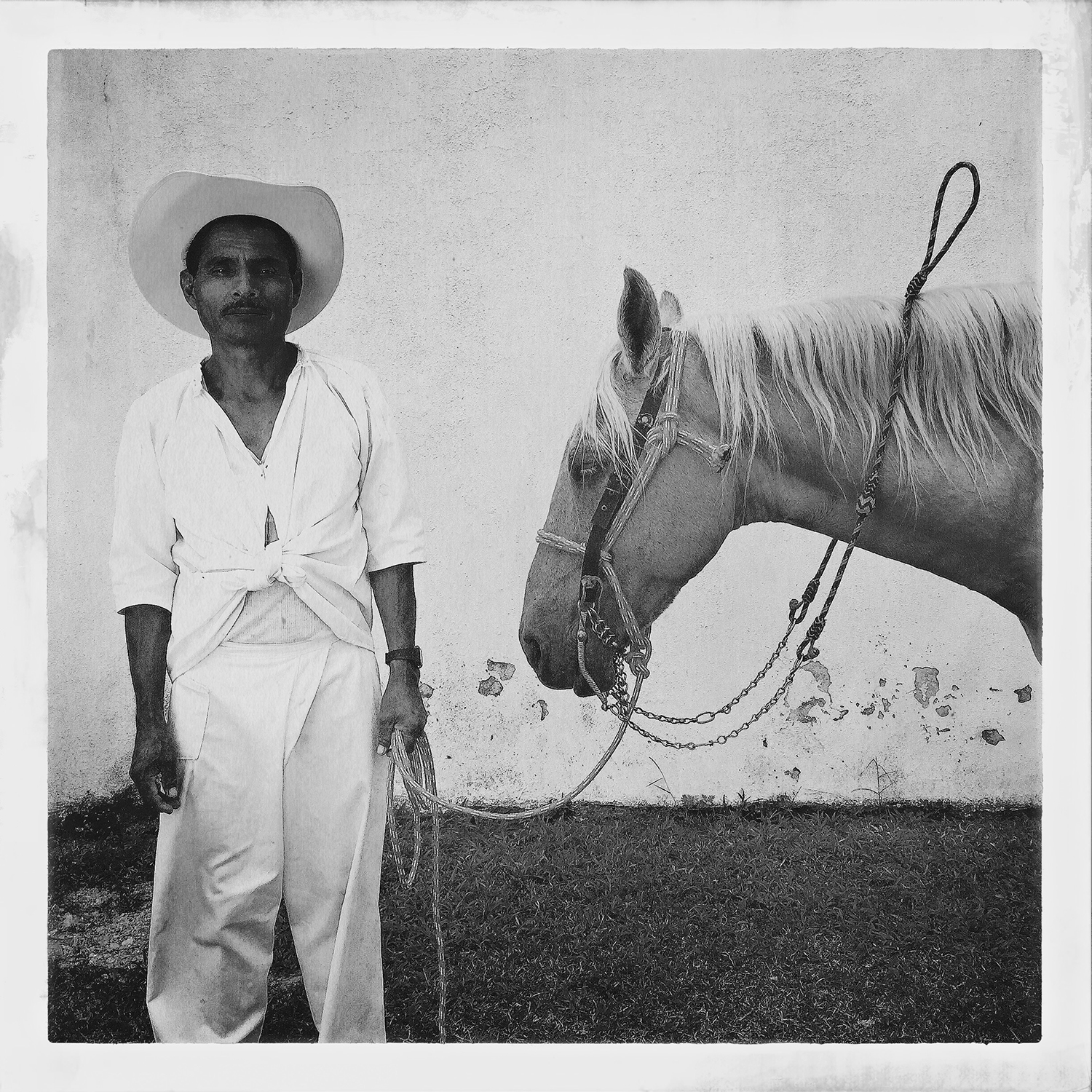

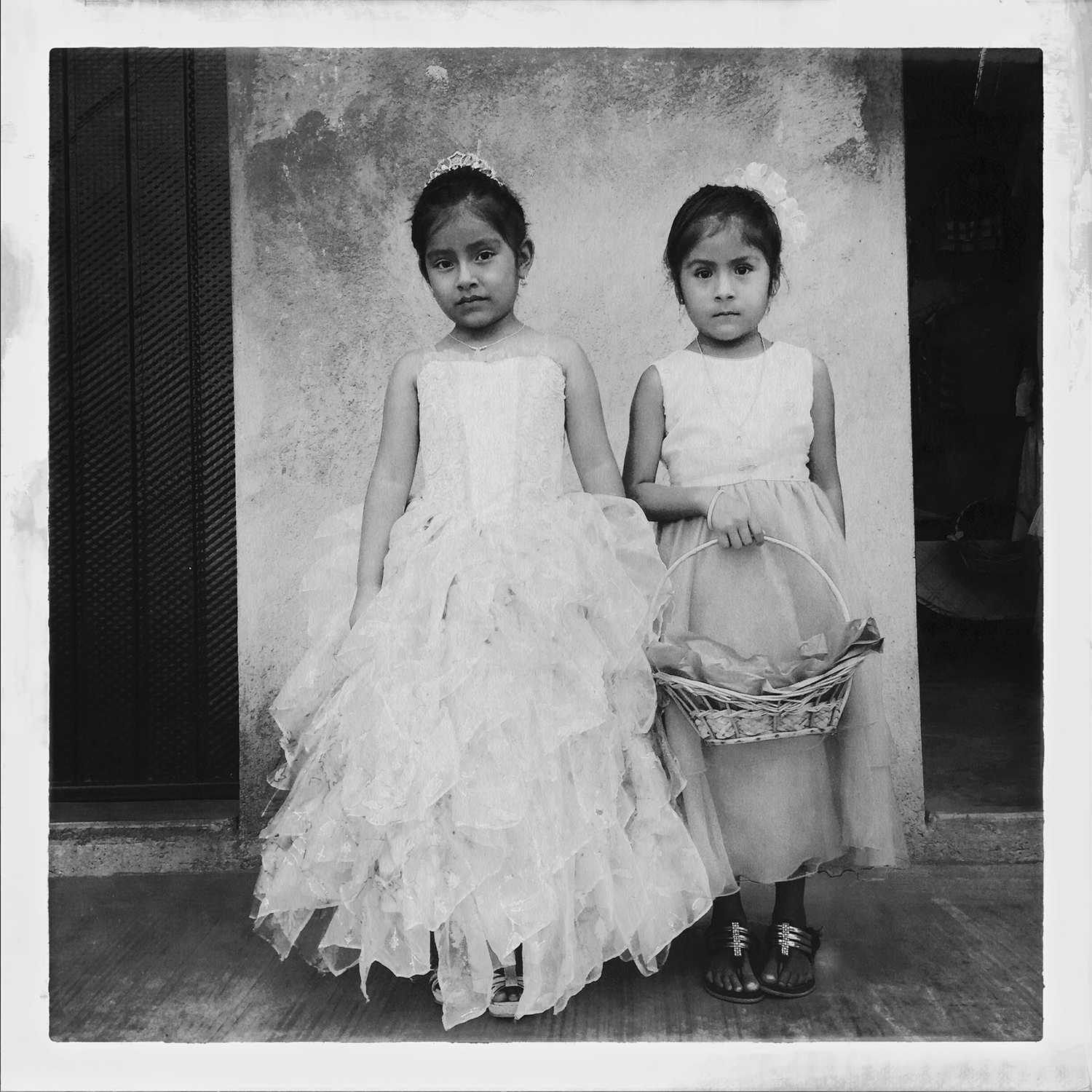

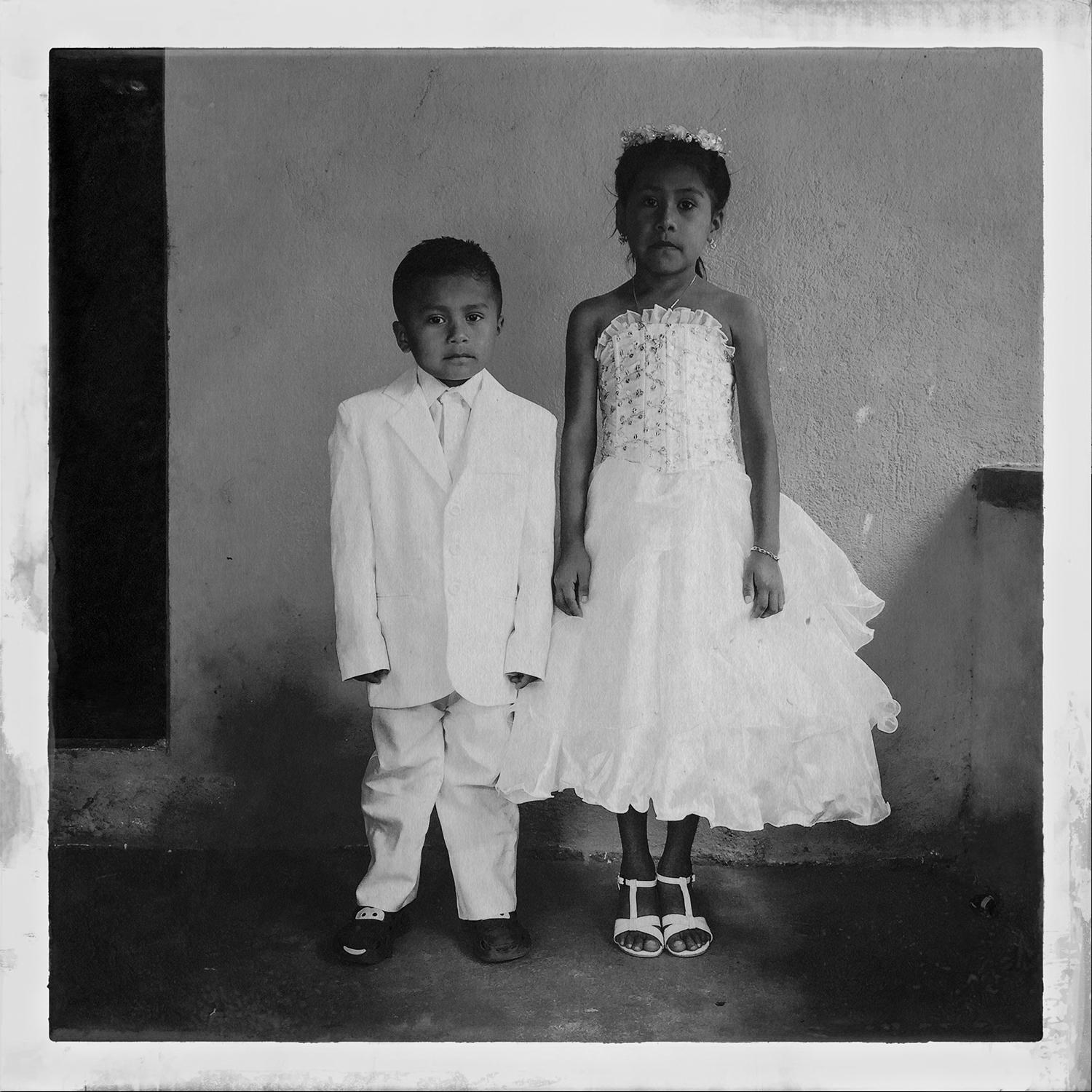

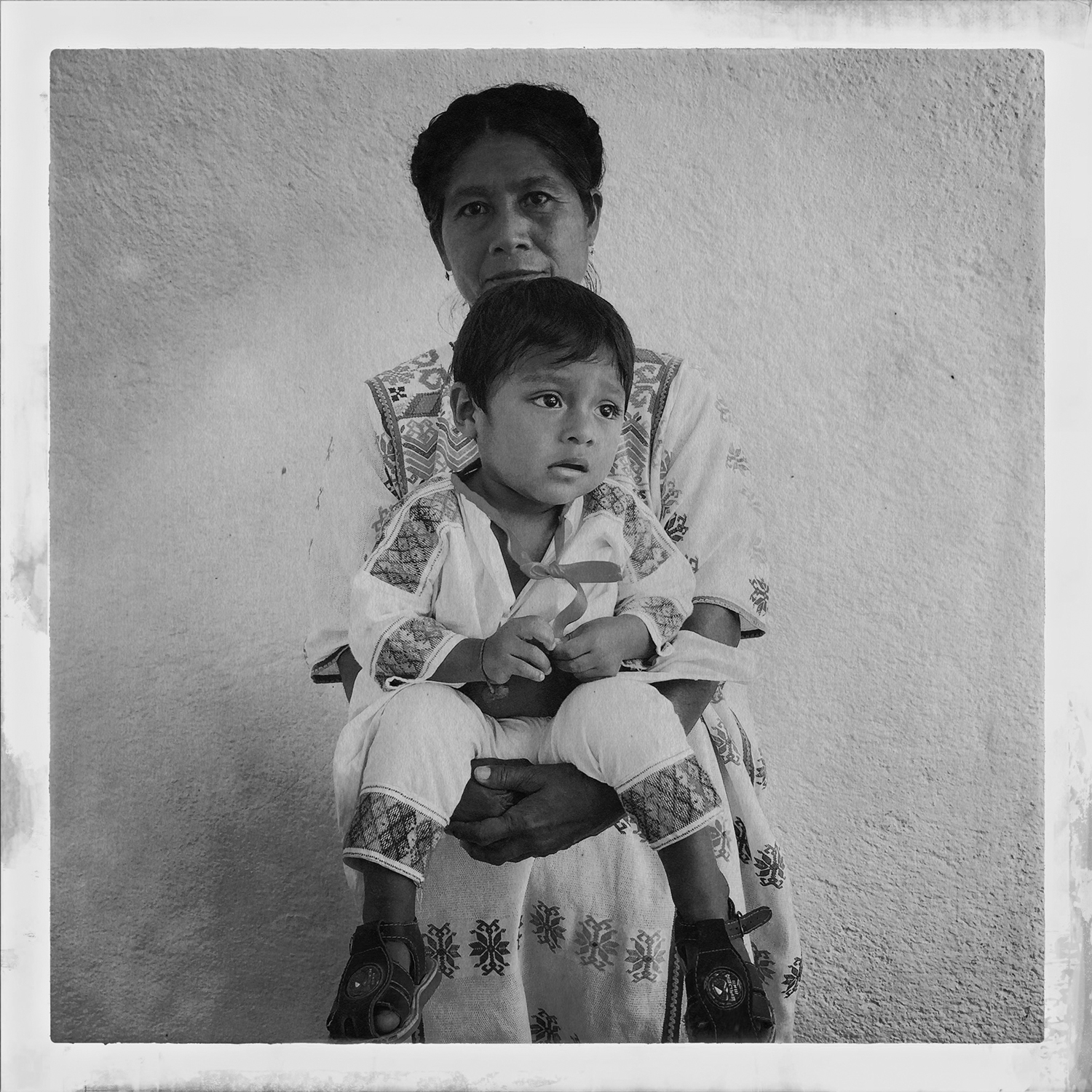

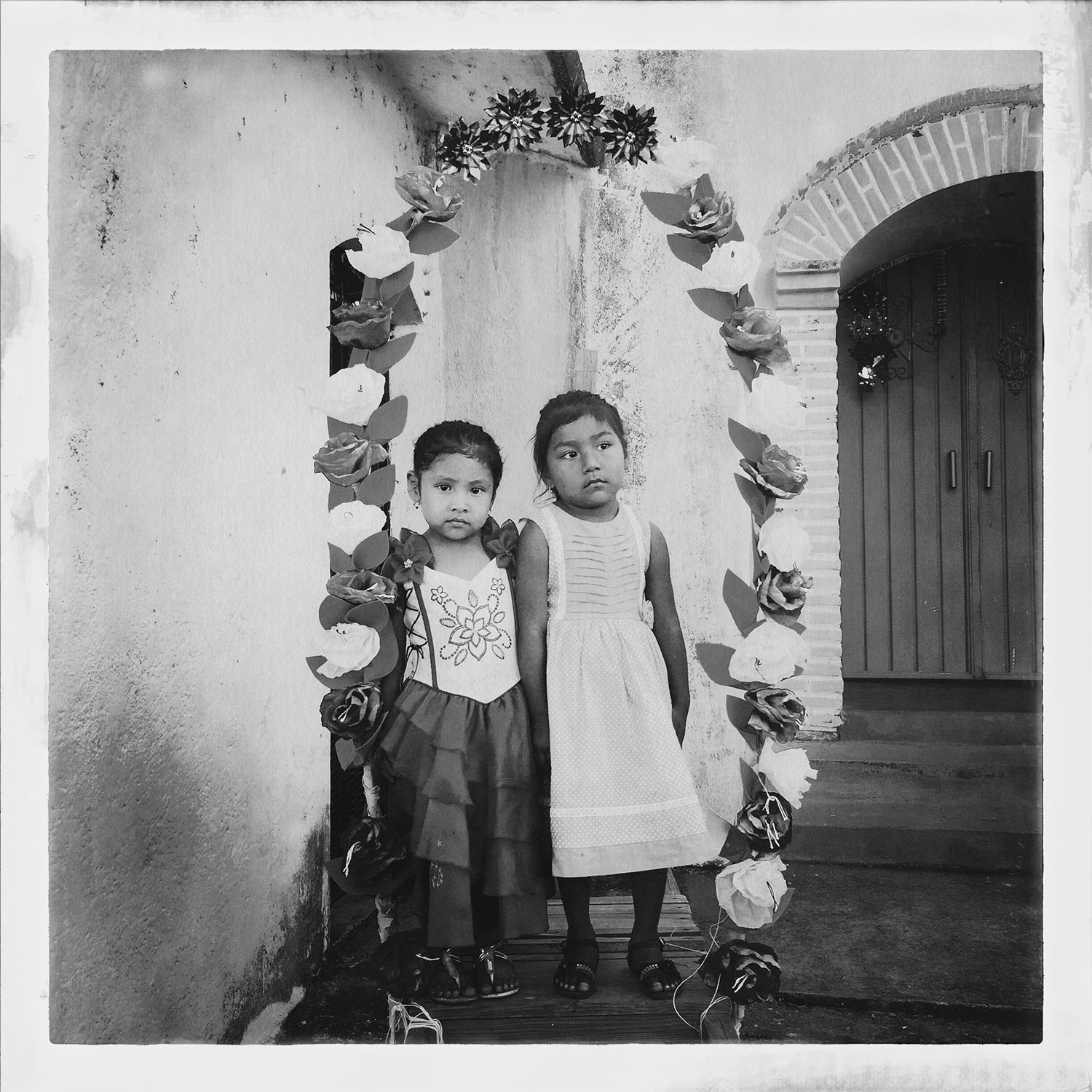

When I finished the story, I went back and handed them a stack of photographs I had taken during those 6 months but their reaction to the portrait I took of them after the first communion was what made me stop and decide to start this family portrait project, using the same tool responsible for the lack of printed images - the cell phone. My idea was to photograph families living in communities surrounded by violence and the real threat of forced disappearances. And to do so with the same artifact they would use to create memories of their regular lives.

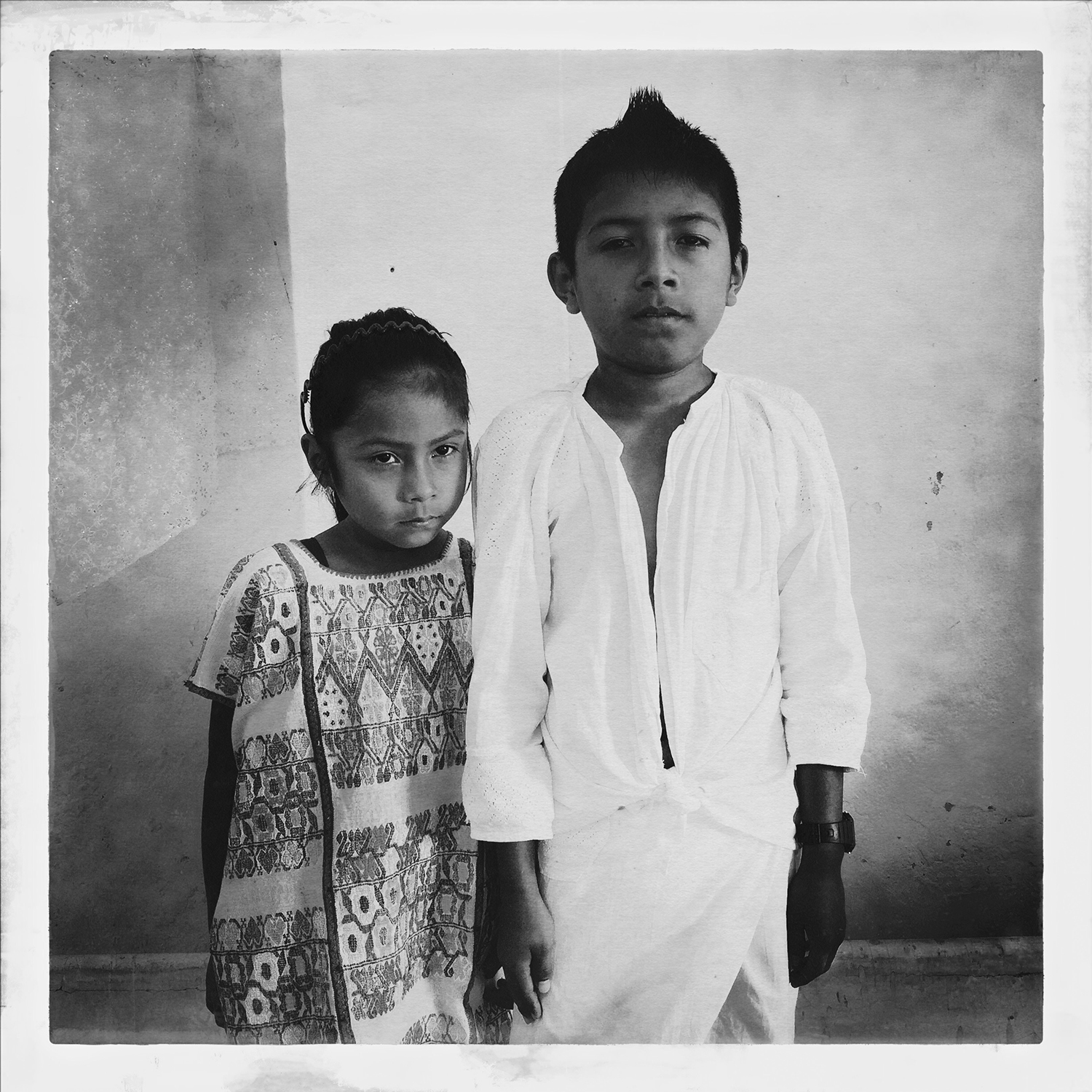

It struck me as a great paradox of the times we’re living in: there has never been so many images produced, photography has never been so popular—we all have cell phones: we’re all photographers—and, yet, fewer and fewer images are being printed. These people were disappearing twice, from life itself and from the memory of their family and friends. Would this be a generation that would only have pictures in a cloud somewhere? Will they take distance from their memories, leaving them in a virtual, immaterial place? Are these children growing up without a family album where later in life they can see themselves and their families and show it to their own children? Will children remember how their parents looked like? Who are we, without our memories?

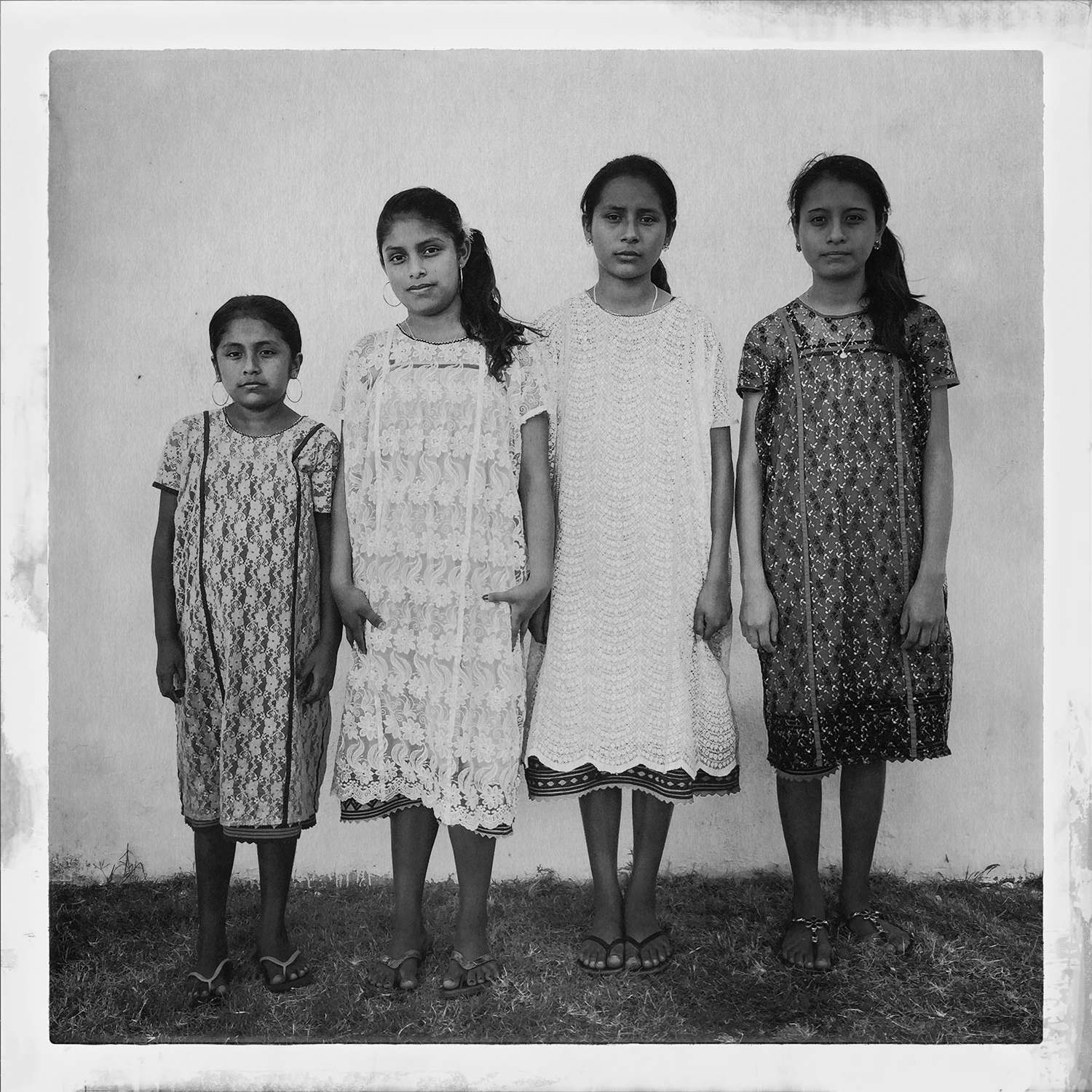

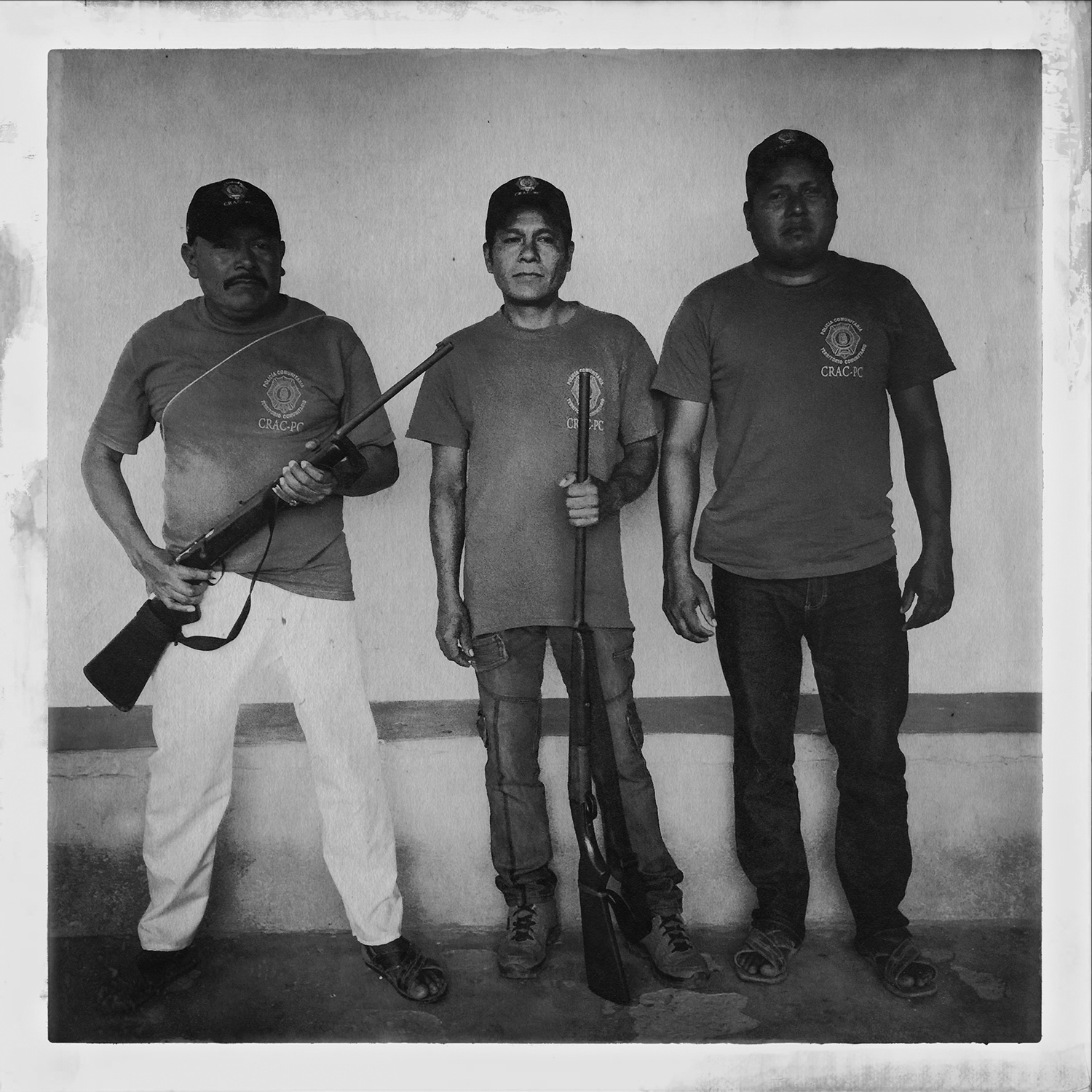

These are people facing daily threats. More than 30.000 people remain missing or disappeared in Mexico since 2006 but the real number is much higher. Many cases go unreported for fear of retaliation from cartel groups or because of distrust in the authorities.

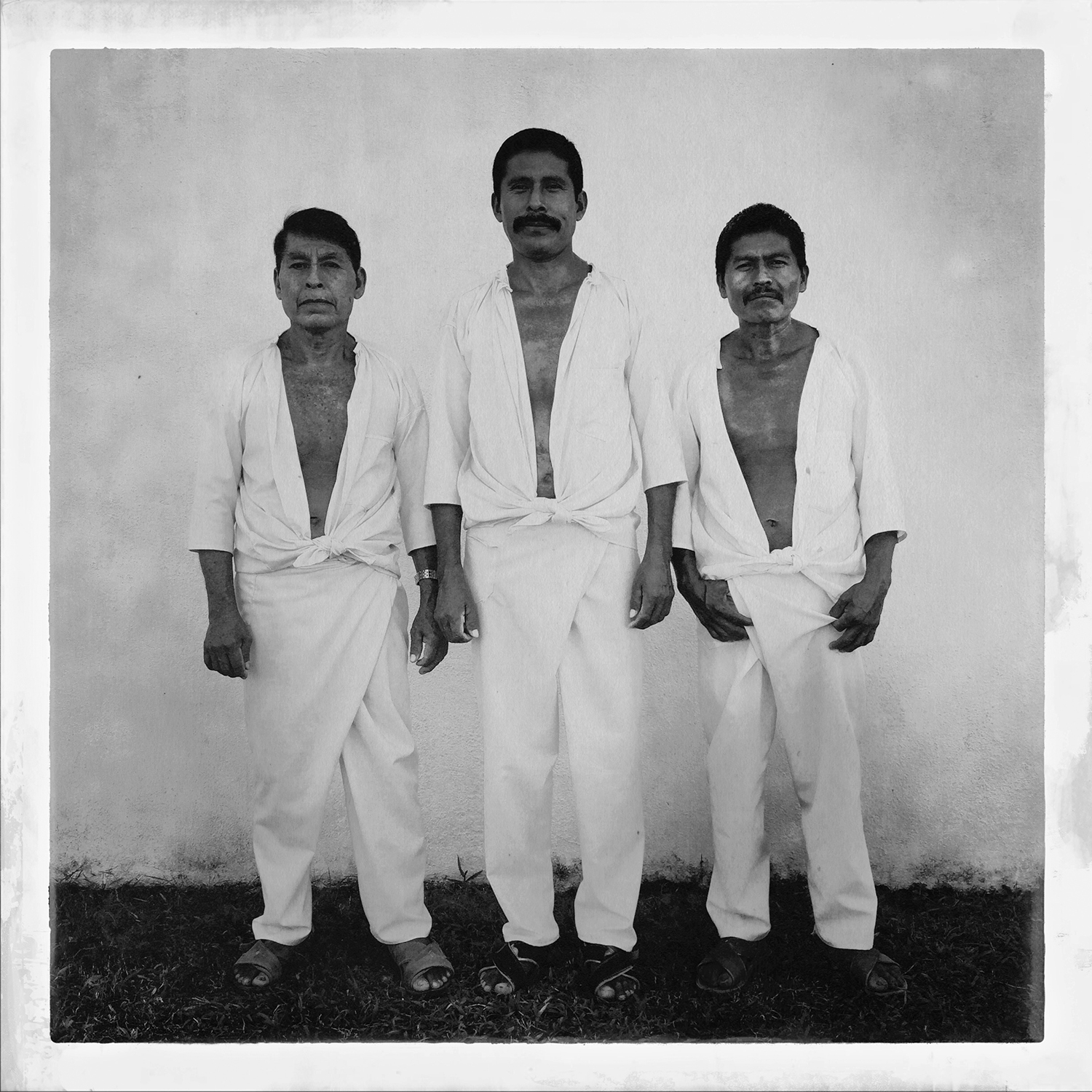

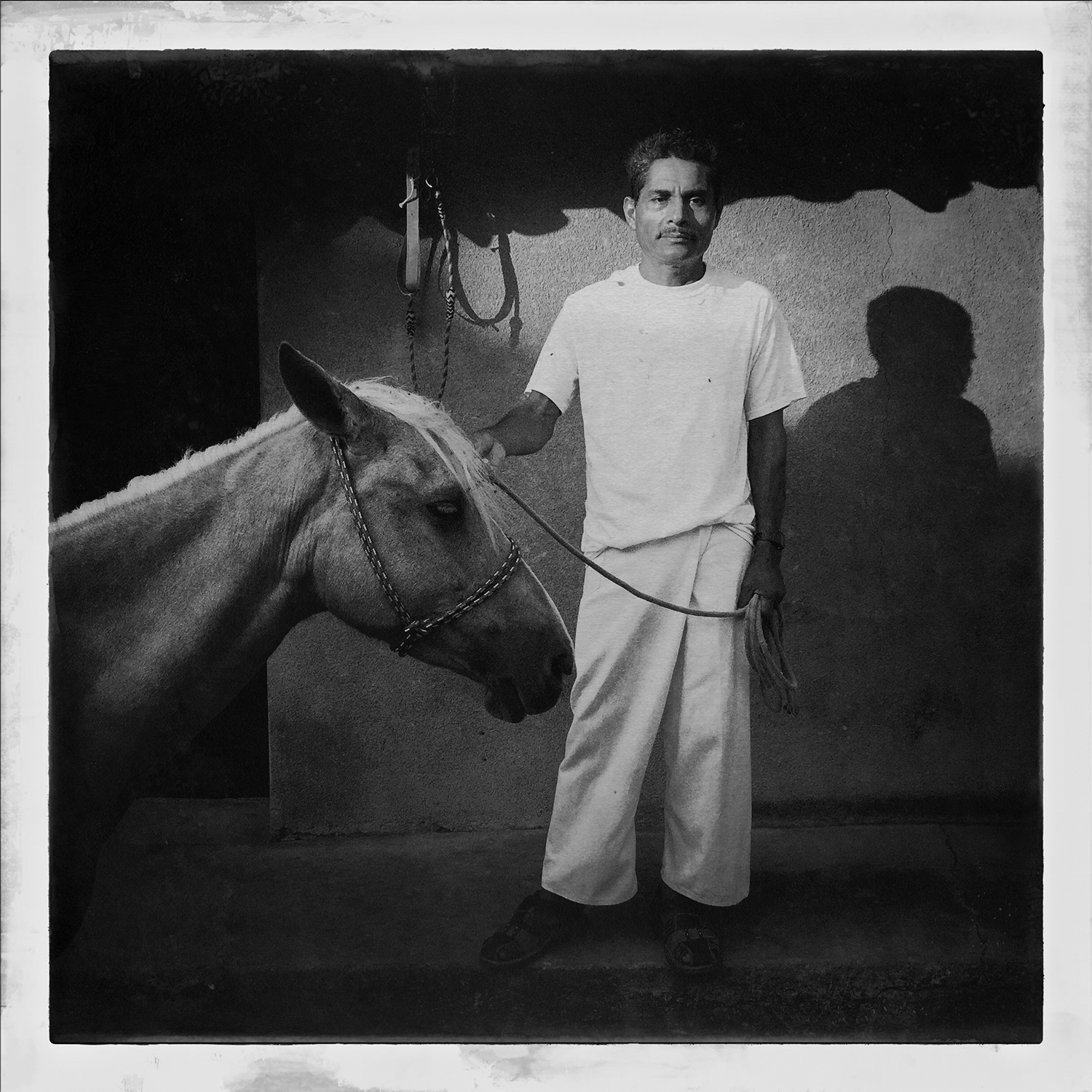

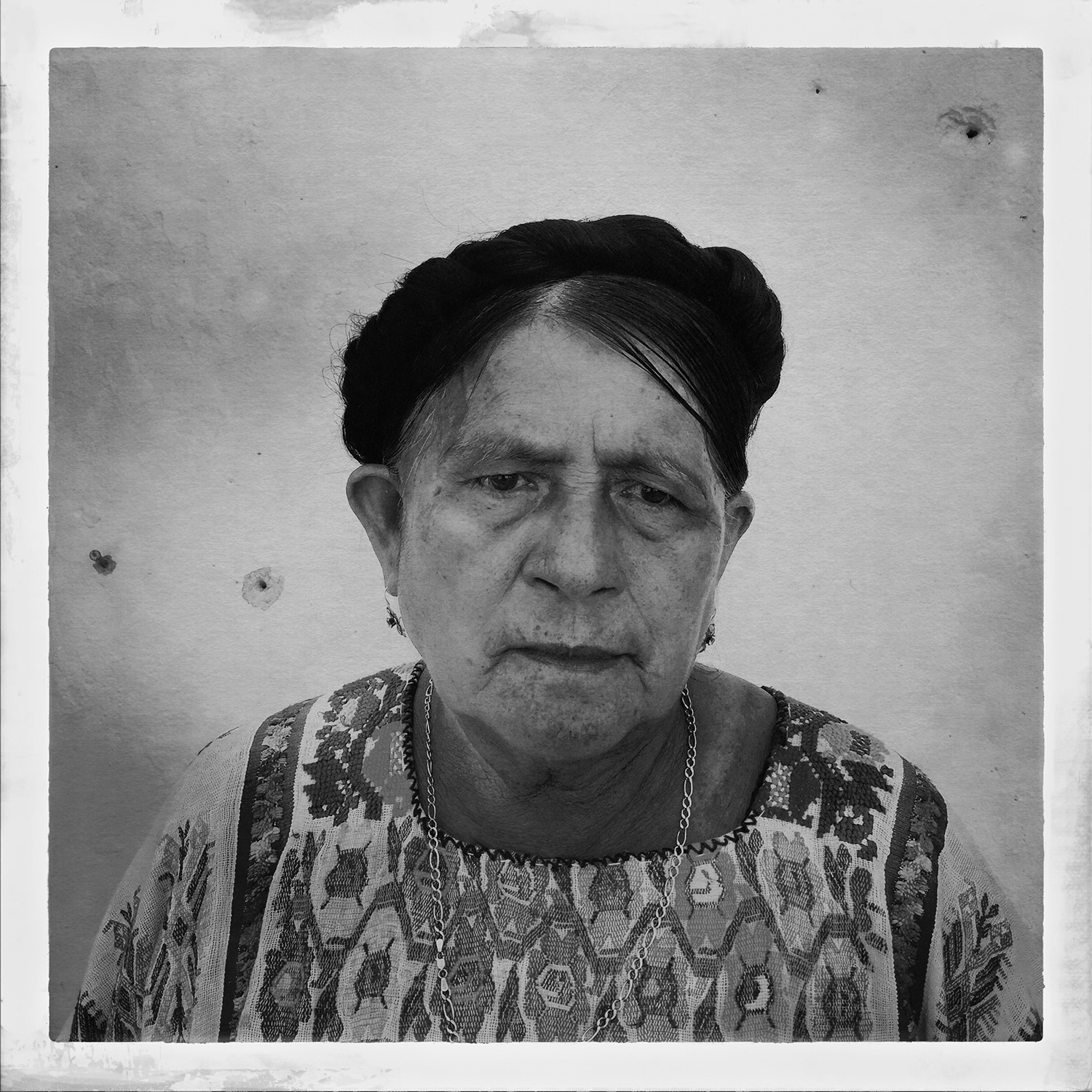

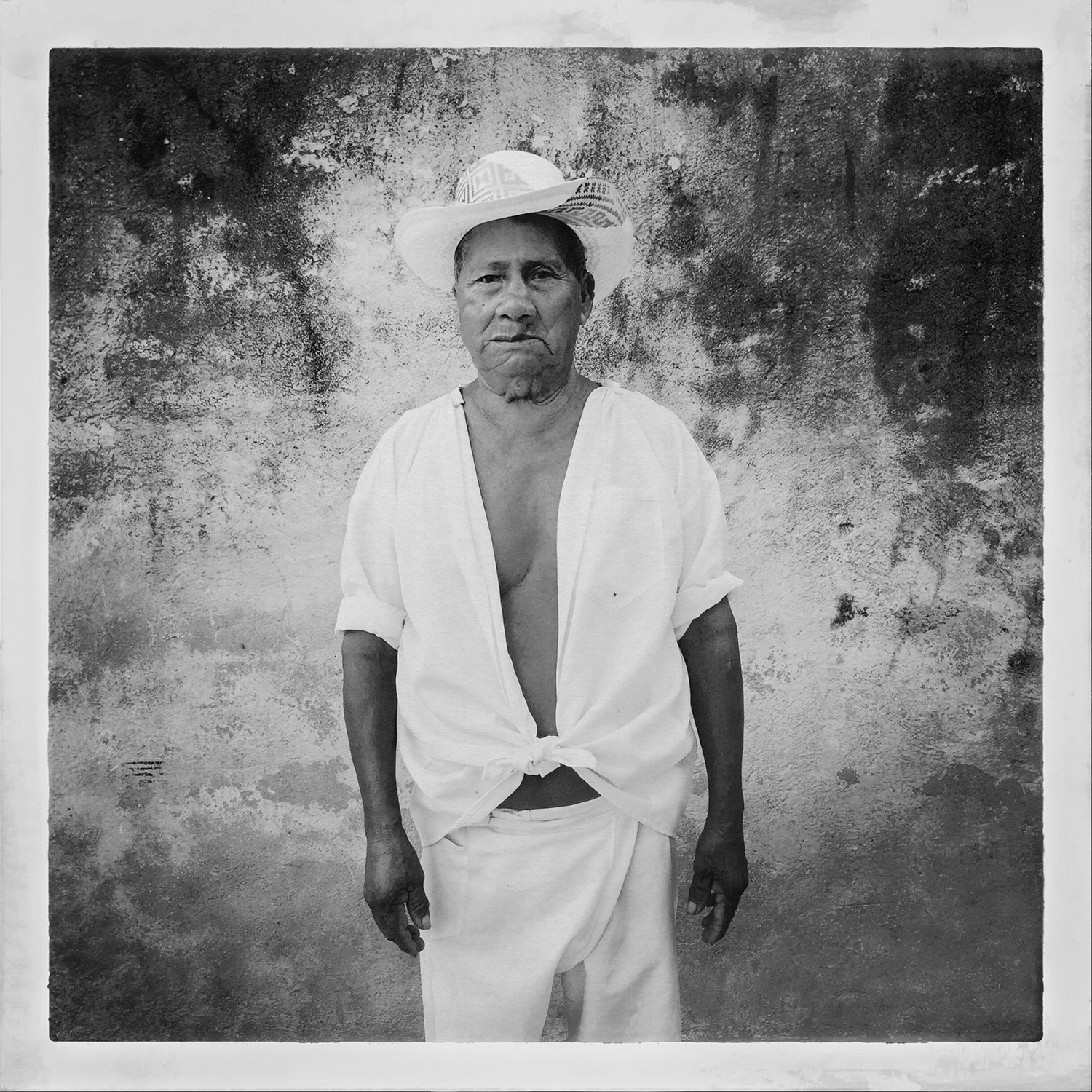

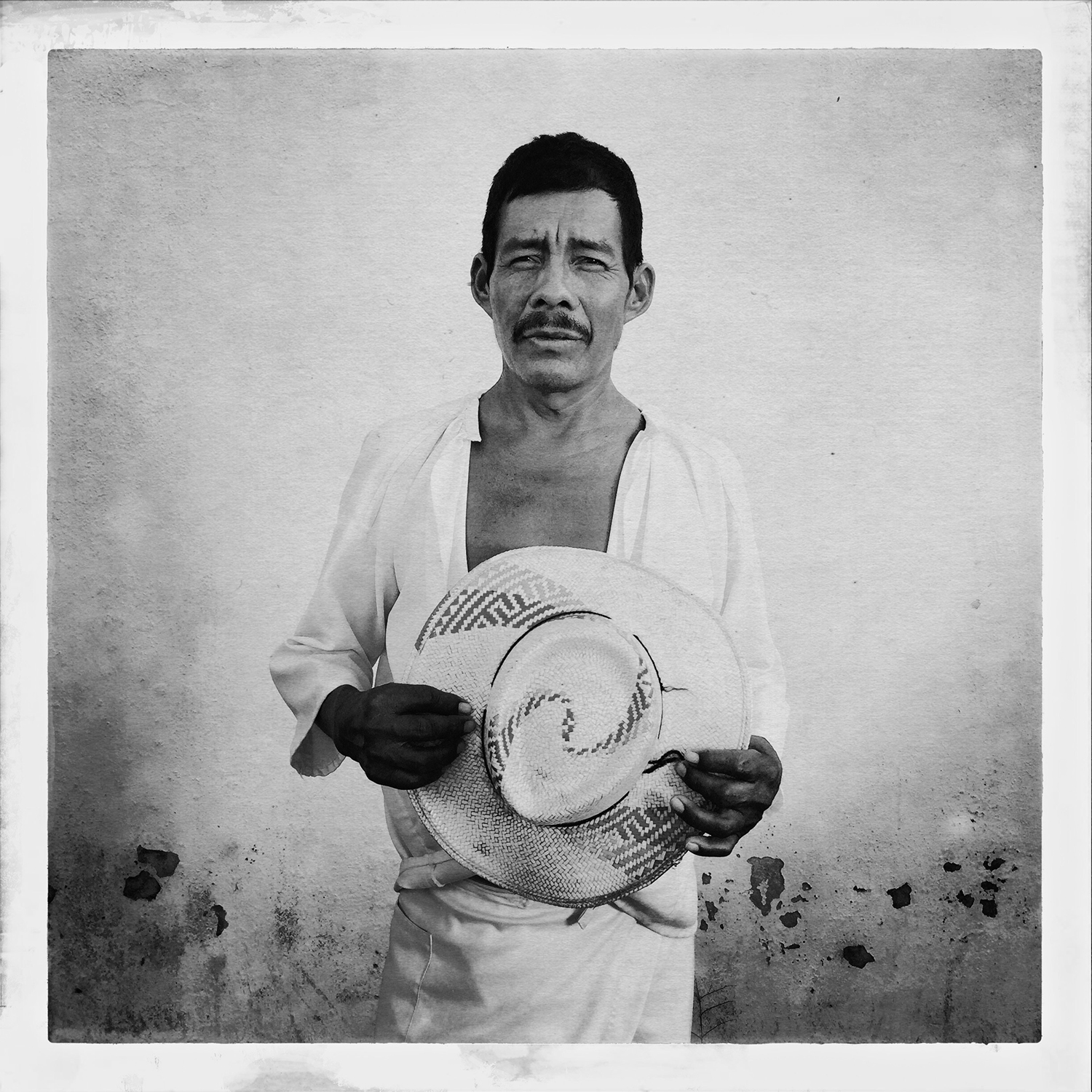

I took the photographs in Huehuetonoc, a small village in the mountains of Guerrero, where the population, from an indigenous group called Amuzgo, created a self-defense group and were able to protect their community from the neighboring cartels and their poppy fields.

A second phase of the project was photographed in two different communities of Colombia, the Wayúu indigenous group of Hatonuevo, La Guajira, and the Afro Colombians from San Basilio de Palenque, Bolivar. Although not presently in direct threat of disappearance by conflict and armed groups anymore, these communities are still a symbol of resistance, struggling to maintain their rich cultural past.

I have always been fascinated by family portraits and how much of our identity they represent. The story told by posed portraits is one of change over time; family groups look different at different times, thus also telling a story about where and how we live. A family portrait is a profound way to define ourselves. In those pictures we say: These are who we are.

A person photographed has achieved a moment of redemption, saved from the fate of being forever forgotten.